On January 25, dozens of students from across the state gathered in the Oakwood gym not to hit the hardwood, but to compete on a bigger-than-basketball-court-sized race track. The teams were part of a qualifying round for the Hydrogen Grand Prix, a global competition organized by hydrogen fuel cell maker Horizon, and sponsored by Toyota Mirai, an FCEV (Fuel Cell Electric Vehicle).

Oakwood was represented by four teams—two from high school and two from middle school—helmed by co-pilots at laptops monitoring the cars’ speed and efficiency, with drivers carefully guiding vehicles around the winding course. As cars zip around the track, they transmit real-time information about speed, fuel usage, and lap times to the pit crews, which they enter into spreadsheets on their laptops. Co-pilots and drivers communicate via headset, relaying data about the cars’ efficiency and speed to the drivers, who adjust their driving styles accordingly.

“Every time you stop and accelerate, that uses a certain amount of energy,” says 8th grader River. “The goal is to be as consistent as possible, while taking the least amount of turns, trying to not go full speed and crashing.”

A team must make 150 laps in a two-hour heat to qualify for Southern-California Regionals, followed by an all-state race, and then the world championships. In the four years Oakwood has participated, they haven’t lost a US race, and have tied for 2nd in the world race in 2018 and 2019. This year’s world championship will happen in the Netherlands in May.

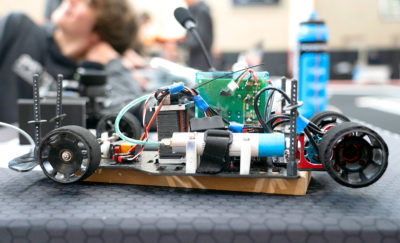

The competition is part of Oakwood’s STEAM program, led by Marcos Arias, and incorporates a wide array of science, engineering, and artistic skills. Throughout the semester, students design and modify their cars, customizing everything from their weight, size, and profile to the type and number of fuel cells and batteries they hold. They begin by designing the chassis, using laser-cutting, 3D printing, and vacuum forming, finally painting the shell to stand out.

“This is our new car, we call it our baby car, it’s super light, super compact,” explains 9th grader Jade, pointing to a small orange car zooming around the track. “We made a conscious decision to shrink everything down, the batteries, everything. Technically we have to make more pit stops, but we’re able to go faster.”

They also must decide how best to utilize their energy sources, between the hydrogen fuel cells and electric batteries, optimizing for weight, battery life, and fuel efficiency, since they are only allowed a certain amount of energy or “watt hours” per race.

“The trick is to balance speed with battery life,” says Marcos. “You want to be efficient AND fast. If you’re fast, but you die early, your ranking will go down.”

This year’s program is a little different from years past. To make the event more like a conventional sports season with regular training sessions, Marcos convinced the Grand Prix organizers to have qualifying rounds every few weeks, half in Northern California and half at Oakwood. Even after a team qualifies by making their 150 laps—which all of Oakwood’s teams have already done— they still meet for the qualifiers, working on making their cars more efficient, and strengthening the communication between co-pilots and drivers. Over the course of these several races, students develop a number of capacities from the physical skill of driving the car and repairing it during pit stops, to the ability to quickly receive, analyze, and convey data.

As much as it is a competition, the Horizon Grand Prix is about teamwork and community, as evidenced by the companionship and information sharing between teams during the qualifiers. As 9th grader Layla exclaims, “It’s exciting to be a part of something so big, so worldwide.”